MAGNIFICATION

A conscious act of seeing

On a series of manuals for photographic preservation, I decontextualized test images and to reveal invisible structures.

I realized that in History of Photography and in Photographic Techniques manuals, space and its internal proportion illustrate the ancillary relationship between Photography and the Theory of Photography. Usually, on a space-page, the narration is mainly verbal, removing power from photographs, compressed into a few centimetres, and crowned with an explanation or justification. Photographs (the topic of research) are paradoxically completely secondary; they are always related to the text and sometimes subordinated to it. My intention is to liberate photographs from their secondary functions and to give them a new poetic identity. As a result, Magnification celebrates (from Latin "magnificat") the aesthetics of the minimal photographic language, its manifestation, its embodiment, and its becoming a trace.

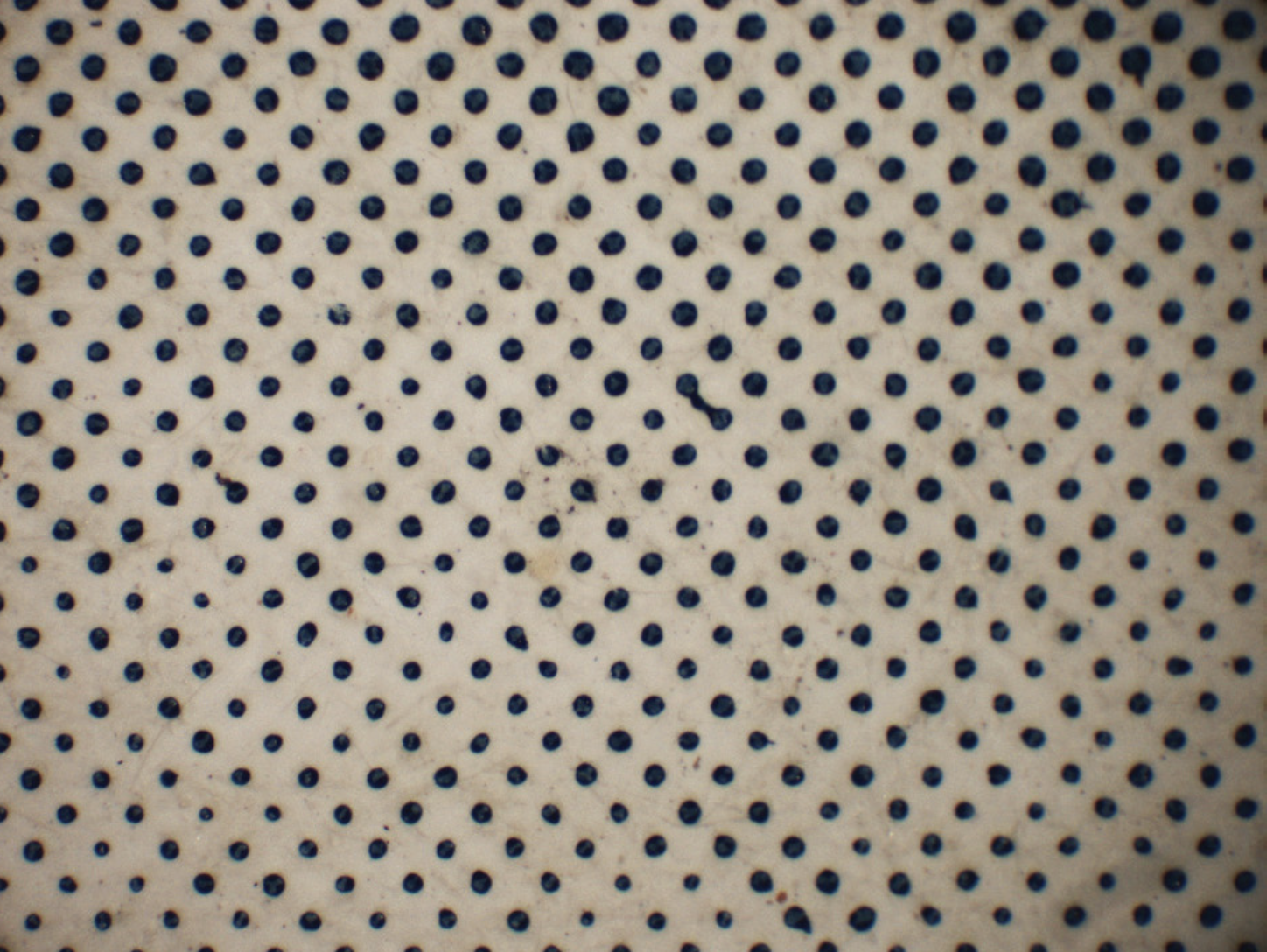

Magnification is a tribute to the blow-up and the bewilderment of the eye in order to understand the original process and the alteration into an abstract image. Enlargements of the earliest photographic processes since the advent of image reproduction: calotypes, photogravures, and halftones reveal an archaic beauty. Squares, dots and lines, colors juxtapose like brushstrokes, like new textures that recall natural surfaces and skins. The eye wanders, fluctuates and lingers on normally invisible details, on the wavy-lines that make a face three-dimensional, on the overlapping of gray and black squares, on the pattern of red and black hair, on the dotted motifs of the cyan wall behind a seated woman, on the superimposition of the four levels of color printing: cyan, yellow, magenta and K (black) to create the roundness of an apple, on the distorted grain thanks to a wide screen used on rough paper which creates the effect of a spotted horse and on the brushstrokes of the hand-painted collotypes.

Magnification is an intervention of the “ecology of the images” to re-see what has already been produced through enhanced awareness of our gaze because enlargement controls the visible and makes the unseen perceptible. The blow-up leads to a model of consciousness based on visibility. The act of enlarging an image is an epiphanic gesture that reveals how photographic technique transforms the real and makes us aware of the metaphor/translation of the real image into a printed image, as well as of abstract aesthetics, regaining a new sense of sight. By removing their context and augmenting their proportions, the test images adopt and display an abstract aesthetic of obsolete techniques, decoding reality, through the téchne in a new, poetic language, in a form of communication that connects us with mysticism. Photography is treated as a medium, as a physical object, whose appearance is linked to the execution of mechanical operations.

Magnification concerns photographic reproduction, the objects it produces, the subjects it involves, and the experiences it creates. The discourse is exclusively photographic, up to digital software that permits giant-size prints, eliminating the boundary between art and documentary photography. The enlargement process contributes to the photo's re-invention. A fragment of the whole image that becomes a new photograph: it is born from the cut, from the re-composition with the original image, and from the exposition in a new context by displacing its semantic field.

Through this series, I was able to validate a thesis already developed in the project on The First Photos, whereby the images chosen for the photographic tests respond, more or less consciously, to an authentic and recurring aesthetic: representations of nature and women (e.g. with ginger hair) and, above all, enlargements of their eyes. Furthermore, test images, like all photographs, have a relationship with their time, revealing an intrinsic relationship with the society in which they were taken. The dating of a photograph, and therefore the dating of its technique, is recognizable through the socio-historical traces left by a fashion object, or a hairstyle, or the composition of a gestalt. The history of photographic techniques is a social history. If the primary role of photography had not been recognized by society, photography would have been used only by specialists in the field, such as the microscope, and it would not have evolved to meet the demands of new forms of communication.

Francesca Seravalle

MAGNIFICATION

L’ingrandimento come atto cosciente del guardare.

Ho scelto di intervenire su una collana di manuali per la conservazione fotografica decontestualizzando le immagini funzionali ai test fotografici e rivelando strutture invisibili.

Mi sono resa conto che nei manuali di storia e tecnica della fotografia lo spazio e le proporzioni interne parlano del rapporto ancillare della fotografia nei confronti della teoria o della tecnica. Riducendo le immagini a pochi centimetri in una spazio-pagina coronata da un testo, si decide di delegare la comunicazione alla parola, sottraendola all’immagine. Le fotografie (l’oggetto della ricerca) sono paradossalmente del tutto secondarie; dipendenti e talvolta subordinate al testo. La mia intenzione è quella di liberare le immagini dalla loro funzione secondaria, assegnando una nuova identità poetica. In questo modo l’ingrandimento (magnification) celebra (magnificat) l’estetica del linguaggio minimo fotografico, la sua manifestazione, il suo farsi corpo, il suo divenire traccia.

Magnification è un omaggio al blow-up e allo smarrimento dell’occhio nel dettaglio per capirne l’origine, e il suo farsi immagine astratta. Blow-up dei primi processi fotografici dall’avvento della società della riproduzione dell’immagine: calotipie, fotoincisioni e mezzetinte rivelano una bellezza arcaica. Quadrati, punti e linee, cromie si accostano come pennellate, nuove trame che ricordano superfici e pelli naturali. L’occhio erra, fluttua e si sofferma su dettagli normalmente invisibili, sulle linee ondulate che rendono tridimensionale un volto, sulle sovrapposizioni di quadratini grigi e neri, sul pattern dei capelli rossi e neri, sui motivi puntiformi della parete ciano dietro ad una donna seduta, sulla sovrapposizione dei quattro livelli di stampa a colori: ciano, giallo, magenta e K (nero) per creare la rotondità di una mela, sulla grana.

Magnification è allo stesso tempo un intervento di ecologia dell’immagine per ri-vedere quanto è già stato prodotto, attraverso una nuova consapevolezza del nostro sguardo, perché l’ingrandimento controlla il visibile e rende l’inosservato percepibile. Il blow-up porta ad un modello di coscienza basato sulla visibilità. L’ingrandimento è un gesto epifanico che rivela come la tecnica fotografica traduca il reale e ci renda coscienti della metafora/traslazione dell’immagine reale in immagine stampata; nonché dell’estetica astratta, recuperando un nuovo potere dello sguardo. Attraverso la decontestualizzazione e l’aumentato delle proporzioni, le immagini test, pur mantenendo la propria natura documentaristica, assumono e rivelano un’estetica astratta di tecniche desuete. Una decodificazione del reale attraverso la téchne in un linguaggio nuovo, poetico, in una forma di comunicazione che ci collega con il misticismo. La fotografia è trattata come medium, come oggetto fisico, la cui apparizione è legata all’esecuzione di operazioni meccaniche.

Magnification è un discorso sulla riproduzione fotografica, sugli oggetti che produce, sui soggetti che coinvolge e sull’esperienza che genera. È un discorso che si svolge interamente con mezzi fotografici, fino ai software digitali che permettono le gigantografie, eliminando il confine tra fotografia d’arte e documentaria. L’ingrandimento partecipa in prima persona ad un processo di reinvenzione della stampa. Il frammento dell’immagine totale, attraverso il blow-up, diventa a sua volta una nuova fotografia: nasce dal taglio, dalla ri-composizione con l’immagine originale, dall’ex-posizione in un nuovo contesto dislocando il suo campo semantico.

Attraverso questa serie, ho potuto avvalorare una tesi già sviluppata in una ricerca sulle prime fotografie, per cui le immagini scelte per i test, rispondono, più o meno consapevolmente, a un’estetica autentica e ricorrente: rappresentazioni di natura e di donne (per esempio dai capelli fulvi) e, soprattutto, ingrandimenti dei loro occhi. Le immagini di prova, inoltre, come tutte le fotografie, hanno una relazione con il loro tempo, rivelando un rapporto intrinseco con la società in cui sono state scattate. La datazione di una fotografia, e quindi datazione della sua tecnica, è riconoscibile attraverso tracce storico-sociali, temporanee, lasciate da un oggetto di moda (come un vestito, un’acconciatura) o dalla composizione di una gestalt. La storia delle tecniche fotografiche è quindi storia sociale. Se il ruolo primario della fotografia non fosse stato riconosciuto dalla società, la fotografia sarebbe stata utilizzata solo da specialisti del settore, come il microscopio, e non si sarebbe evoluta per soddisfare le esigenze delle nuove forme di comunicazione.

Francesca Seravalle